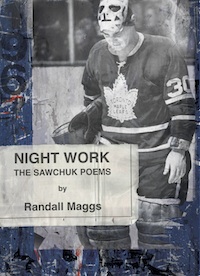

In Night Work: The Sawchuk Poems, Randall Maggs gives voice to one of the greatest goaltenders of all time. While Terry Sawchuk’s position and the inner demons he battled separated him from the others on his team, he was also silenced by his early death in 1970 at the age of 40. While other players have gone on to tell their own stories, to see their careers recognized by the Hockey Hall of Fame, Sawchuk never had the opportunity. In this stunning collection of poems, which Stephen Brunt has suggested may be the “truest hockey book ever written,†Maggs knowingly and ever so skillfully negotiates the border between voice and silence, between story and history. In a number of key poems, Maggs brings closer the surface this tension between what we know (or believe we know) about Sawchuk and his own hesitant desire as a poet to see this history through Sawchuk’s own battered eyes.

As Maggs reminds us so eloquently in the linked poems “Big Dogs (1)†and “Big Dogs (2),†this is not simply a question about how to get into the mind of a long dead, tormented hockey genius; it extends to how well we can ever understand the past, even when we’ve lived it ourselves. The “Big Dogs†poems tell us the story of the poet’s interview with Red Storey, a tremendously gifted athlete in his own right who refereed in the NHL from 1950 to 1959. Storey, who is 83 years old in the interview, spends a great deal of time in silence during the conversation as he works to remember the events of fifty years earlier. Maggs records these silences as Storey “listens a moment to the noises in the hall†(Maggs 59), “looks down at his hands again and around the walls†(60) of his home, or “sits back in his chair, the big head nodding slowly, remembering†(62). These moments of quiet contemplation are punctuated by stories that emerge one by one from the darkness of memory. In what I think of as a quite moving part of these poems, Maggs also inserts into this dialogue the interviewer’s own imaginings of what Red Storey might have wanted to say if he could. These sections, italicized to distinguish them from the other levels of narrative, fill in some of the gaps, but also add another dimension to how we see Storey. They give us the voice of a younger, more articulate man in a way that both pays tribute to the interview subject but also point to the poet’s own longing for someone to be able to speak to him in such an eloquent way.

One of the most fascinating parts of the “Big Dogs” poems that tell us a great deal about the limits of memory and perspective comes in the second poem. Storey tells Maggs about a night in Montreal when, as the game is about to get underway, “Terry skates out from his net to ask me a question I’ll never forget†(110). Storey recounts that a few days earlier, when clearing the crease of the players who’ve piled on top of the goaltender after he made a save, he asked Sawchuk if he was all right. Sawchuk’s angry response to Storey to “go fuck yourself you drunken son of a bitch†(111) earned him a misconduct. Storey describes how, a few days later in Montreal, Sawchuk asks why he received a penalty: “‘What was it for, you big Palooka?’ I say? You told me to eff off. You can’t say that to a referee.’ What I was really wanted to say was you can’t treat friends that way. He just stares at me a moment and you know how dark and scary his eyes could be, I don’t even know what he was feeling, sad or sorry or angry. ‘I don’t remember that. I don’t remember any of that’†(111-12). Storey is haunted all these years about this incident not just because of what this revealed about the dark side of Sawchuk’s personality, but from the dramatic collision of his own (and probably very accurate) memory of Sawchuk’s verbal attack and Sawchuk’s perception of the same event.

The question of how one to reconcile two completely different descriptions or perceptions of a single moment also emerges as a theme in Maggs’ poem “Desperate Moves.†Jacques Plante is being interviewed alongside Terry Sawchuk on what Maggs reminds us is “Hockey Night in English Canada†(64). Plante enthusiastically describes Sawchuk’s game-winning save on Dave Keon:

“The greatest save I ever saw

in hockey,†says Plante, waving pages of notes

in his trapper hand, the black suit too tight and the tie

too narrow, emphasizing an angular face and a startling

inelegant sprawl as he tries in a chair to show Ward Cornell

just how Sawchuk, flat on his back in a pileup

in front, puts a pad high in the air

to save the game. (64)

Perhaps out of embarrassment, sheer modesty, or out of spiteful competitiveness with Plante, Sawchuk, who’s “come straight from the ice in his gear for a rare interview†(64), dismisses his rival’s effusive praise. “I just stuck up a leg†he replies and then adds “You know yourself, Jacques, it’s better to be lucky than good†(64). Not only is Sawchuk’s interview a rare event, but so too is this face-to-face meeting with the two goaltenders who now, rather than seeing who can stop the most pucks, battle over who controls the interpretation of Sawchuk’s heroic save. Plante is clearly frustrated by Sawchuk’s unwillingness to accept his generous compliment, and asks if Sawchuk is suggesting the save was nothing more than a “desperate move.†Sawchuk, deftly smothers the verbal puck in this battle of interpretation by making sure his is the last word. “That’s it, Jacques, Sawchuk says, all in one motion / detaching his mike and rising up out of the ill-considered chair, / “that’s all it was†(65).

Sawchuk’s reticence to speak in any great detail about his performance, of course, also reminds us of the challenges inherent in Maggs’ broader attempt to imagine how Sawchuk saw his own life and achievements. You can almost picture Sawchuk, were he alive today, similarly brushing off any attempts to describe him as having been an amazing athlete or fascinating character. As Maggs carefully imagines his way into Sawchuk’s mind and also this key era in the game’s history, I’m reminded of Demeter’s question about the relationship between art and the subject of art in Robert Kroetsch’s 1969 novel The Studhorse Man. Writing of what he refers to as the “superlative grace and beauty of Chinese art,†Demeter, the narrator, comments “Those old Chinese artists, they drew their horses true to life, true to the rhythm of life. They dreamed their horses and made the horse too. They had their living dream of horses… Ah, where to begin? Why is the truth never where it should be? Is the truth of the man in the man or in the biography? Is the truth of the beast in the flesh and confusion or in the few skillfully arranged lines?†(Kroetsch 155). In Night Work, Maggs’ poems suggest that this is a question that we can never fully answer. Nevertheless, the portrait of Sawchuk that emerges is so rich that it’s hard for any attentive reader of the book to walk away without thinking that, as Stephen Brunt puts it plainly, “his Sawchuk is real.â€