The Canadian Experience: A Northwest Passages editorial

In 1995, my best friend Rob Stocks and I co-founded Northwest Passages, the only bookstore in the world to specialize exclusively in Canadian fiction, poetry, drama, and literary criticism. Since then, Rob’s partner Sarah Bagshaw has taken over all the day-to-day operations of the store, while Rob and I stay involved on many fronts. One of my jobs that I don’t do as well as I would like is to look after the Northwest Passages newsletter which goes out to nearly 1000 readers. It’s supposed to be monthly, but recently semi-annually might be closer to the truth. At any rate, here’s my editorial for this month’s issue:

The Canadian Experience

10/17/2007, somewhere just south of the NY/Quebec border

I’m writing to you today from the front seat of a 54 passenger bus that is taking me, two colleagues, and twenty-nine American students from Burlington, Vermont to Ottawa. In a few hours, our group and the group from the packed bus driving just ahead of us will be sitting in Question Period in Canada’s House of Commons. Our goal in this three-day field trip, run by the University of Vermont Canadian Studies program for more than 50 consecutive years, will be to learn something about Canada, its political institutions, its art and culture, and its national identity.

As I sit on the bus watching the gorgeous fall foliage roll by as we wind our way through Northern New York state, I can’t help but wonder, as I do on this bus trip every October, just what kind of understanding of Canada my students will gain from their time at the National Gallery, the Museum of Civilization, Rideau Hall, and, of course, an Ottawa 67s hockey game. All of the eighty or so students on this trip are taking courses on Canada this fall; some are taking our larger lecture courses on Canadian history, politics, and literature while others are taking one of two first-year seminars on Canadian history and Canadian culture. As few have ever spent time in Canada before, their main knowledge of the country so far comes from what they have learned in class. Will this practical experience complement or contradict the theoretical? Will Ottawa live up to or radically differ from their expectations? How will the sights and sounds of these three days work their way into the students’ overall understanding of Canada?

Questions such as these have preoccupied Canadians for as long as the country has existed; our understanding of ourselves seems all too often to be inextricably tied to how others see us – or, more precisely, to how we believe others see us (or don’t). Think of the popular Molson Canadian advertising campaign in which “Joe Canadian†rants that “I have a Prime Minister, not a president. I speak English and French, not American. And I pronounce it ‘about’, not ‘a boot’†before concluding with the exclamation “I am Canadian!â€

Although witnessing Question Period in action – something I recommend all Canadians do in person whenever possible – usually reminds me that our Members of Parliament are too busy with what’s happening within Canada to concern themselves a great deal with how Canada is perceived internationally, in every one of the Question Periods I’ve attended with my students we have heard at least one angry exchange between the government and opposition parties about how Canada sets its own agenda and “will not be taking direction from George Bush!†This predictable attempt to make the government look bad in the eyes of Canadians always elicits surprised looks from my students. Although I don’t think my students ever perceive this to be “Anti-Americanism,†they are nevertheless surprised to see the degree to which the relationship between the two countries is never far from the surface of any political debate.

One thing that always strikes me during our class visits to Ottawa is that, for the most part, the entirety of my students’ knowledge about Canada has come from a single course on Canada and, for some, the three-day trip to Ottawa. If one’s goal is to give one’s students a solid grounding in Canadian history, politics, or literature, then, the stakes when planning a course or a class trip are significantly higher than when one engages in similar activities back in Canada. If one doesn’t get a chance, for instance, to spend much time with the paintings of Tom Thomson or Emily Carr at The National Gallery, or to include Margaret Laurence or David Adams Richards in one’s Canadian literature course, someone in Canada can hope that his or her students will be exposed to this content at another point in their lives, if they haven’t been already. When working outside of Canada, where the works of Margaret Laurence aren’t even available and most art history professors have never heard of The Group of Seven, one can’t help but think that if one doesn’t include something in one’s course that there is virtually no chance that the students will ever encounter that idea, historical event, or work of art anywhere else.

The design of my curriculum (and field trip itinerary) is something that weighs heavily on me, but then again it always has, long before I ever imagined I’d be teaching in the US. It’s clear to me, and is to many of my colleagues back home in Canada that, even if students may encounter other books, paintings, or arguments in other contexts, the weight that one places on something by including it in a course is hard to overcome. Regardless of how many other works one encounters outside the classroom the content we have been taught (and teach) in the classroom will almost always seem to be more “important†than what we find on our own. Even though I regularly attempt to disabuse students of this notion by suggesting alternate choices I could have made, by having the students themselves help design the curriculum of my contemporary Canadian literature course, and by requiring them to do research and report on things that I’ve left out of the picture of Canada I’ve created for them, the impact of the “official†curriculum is hard to match.

One can apply this same argument to the effect that shortlists for literary awards like the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Governor General’s Award have on the literary landscape of Canada. As much as we might try to argue that any shortlist is simply one jury’s take on the books from that particular year, the choices that jury makes have an an impact on the recognized books and authors that can last for years to come. For many people outside of Canada especially these lists serve as a snapshot of the Canadian literary scene for that particular year, whether or not these books are truly representative of what was published in Canada during that time. Take a look at the shortlists included below. What picture of the literatures of Canada do these lists paint?

Unless you’ve read all of these shortlisted books and the many books that didn’t make the cut, it’s hard to pass much judgement on the merits or shortcomings of these lists. Awards season, though, never fails to excite readers, booksellers, and publishers (me included). And for that alone, I find it impossible to find much wrong with the whole process of literary awards or, for that matter, an intensive field trip focusing on the “most important†sites in our nation’s capital. If these create an enthusiasm that the intended audience will continue to explore in the future, then that alone makes the exercise well worthwhile.

Postscript 10/30

The trip was a huge success and since our return I’ve also hosted the Grand Chief of the Grand Council of the Crees, Matthew Mukash, at UVM where he spoke to an audience of over 200 students, many of whom were with us in Ottawa. This great opportunity to have the Grand Chief here provided a valuable supplement to our Ottawa experience and, I hope, will mark the beginning of a long-term relationship between UVM and the Quebec Cree.

The students came back from Ottawa deeply impressed by what they saw and experienced; everyone who met them along the way, I’m equally happy to report, was just as taken by the group of American students who could tell them things like which four provinces were the first to join confederation or converse about everything from the Throne Speech to Stephen Leacock’s Sunshine Sketches of a Little Town.

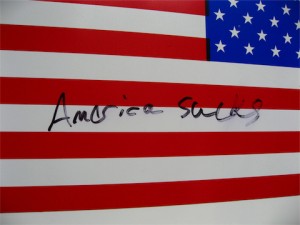

At the same time as this experience gave us all hope that these students will go on to become goodwill ambassadors for Canada as they go about their lives in the USA, we were also met with a sober reminder not only of the ongoing tensions between the two countries, but of the challenges these students will face in a world not currently enamored with the policies of the US administration. As we boarded our bus to head back to Vermont, we noticed that someone had taken a marker and written “America sucks†over the small American flag beside the bus door.

Perhaps more than all the other class trips I’ve been on, the students headed home with a different perspective of Canada, but also of the United States.